In the summer of 2021, trainee GP Emma set out to walk all 600km of the Slovenian Mountain Trail. Over an eye-watering 37,000 metres ascent, she braved crazy weather, unclear paths and unexpected detours. However, this incredibly tough solo journey was in truth only a small part of what pushes Emma forward.

Here, she kindly opens her heart to give a truly moving insight into her personal struggles, in the hope that it’ll help others find their voices.

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilised people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity” John Muir

This quote certainly resonates with me and I’m sure it does for many of you too, particularly after the last eighteen months. It was definitely one of the reasons I found myself heading off on a long walk alone through the Slovene Mountains. I’ve spent a lot of time, both on the trail and afterwards, reflecting on the journey and the people and events in my life that led me to make that decision.

I certainly wouldn’t say my childhood was a typical one. I am the third generation, following in the footsteps of two female trailblazers, both of whom are huge influences in my life.

My grandmother Kathy was in her twenties when her alcoholic husband walked out, leaving her to support two young kids. From this low point, she completely rebuilt her life, working three jobs to regain her independence and support her children.

She had a love for exploring and was an avid solo traveller, visiting South America, Mexico, India, Hong Kong and Tibet at a time when women were largely expected to stay at home and be good wives.

Similarly in her twenties, my mother Carole left the UK and worked for a year as a nurse in a Cambodian refugee camp after the genocide there. She went on to build a successful career as a leader in public and global health, all whilst raising three children largely on her own with no real financial or emotional support from my father after they divorced when I was twelve. Both of these women have given me a love for exploring, immersing myself in new cultures and learning from the people in them. They’ve taught me that it’s ok to not follow a traditional path in life and how to be independent, resilient, kind, and to live a life true and authentic to oneself.

However, I didn’t feel like that for a big part of my life. In fact, I often felt quite displaced and unsure of myself. My mum’s career meant we moved around a lot when I was young. At three weeks old, I left the UK for Nepal, then Pakistan and on to Zimbabwe and so I grew up surrounded by beautiful towering mountains and nature.

But I also witnessed a lot of poverty and health inequality that partly led to my decision to become a doctor later in life. I certainly didn’t have a straightforward answer to where home was. We uprooted our lives every four years on average. That meant new schools, new friends, new pets each time. Not long after my dad left, the worsening political situation in Zimbabwe meant my siblings and I had to go to boarding school in England. We were put on a plane as unaccompanied minors and arrived in a country that felt totally foreign to me, having never lived here.

A FISH OUT OF WATER

I was a fish out of water. The weird kid from Zimbabwe with a strange accent, different clothes. I was initially bullied but I think those years shaped my next twenty, teaching me that to survive, you've got to fit in. And so I conformed and moulded myself to become like those around me. I started to lose all sense of myself, I forgot the amazing people and places that shaped me growing up. I lost my interest in the outdoors because apparently, it wasn't cool, and I spent my weekends in shopping centres or drinking in nightclubs, doing what everyone else did.

In 2013 I graduated from medical school and set out as a fresh-faced junior doctor. Like many, I was driven by a desire ‘to do good’, but in truth, I had no idea how different the reality would be when compared to my somewhat idealistic and naive expectations. I had an intense and steep learning curve with a lot of imposter syndrome. There was also exhaustion - thanks to regularly doing twelve days of consecutive shifts, and I developed quite bad insomnia. However, I was learning a lot, I was mentally stimulated, I enjoyed the variety and meeting people from all walks of life.

I had always thought of myself as a high achiever but it can be a lot to deal with, and I’m not sure medical school really equips young doctors to deal with some of what we have to face. Over the next few years, the realities of working in an underfunded, under-resourced, understaffed NHS started to hit. I wasn’t really enjoying medicine as a career but dedicating eight years of university study and amassing a substantial mountain of debt will keep many struggling doctors trapped in a feeling of trapped-ness. I developed severe insomnia working a brutal A&E rota that was turning my body clock inside out and upside down.

Outside of work, things were also compounding, although I failed to recognise the impact this was having on my mental health. A long-term but quite unhealthy relationship finally broke down. I was suppressing my sexuality and not dealing with family issues. There was so much I had never processed or dealt with in my life, or spoken to anyone about. I stopped exercising, ate terribly, and things slowly started to unravel. I distracted the pain of exhaustion with alcohol after my shifts which led to worsening and chronic sleep deprivation that made me feel hopeless and more despairing. The little time I had off was spent trying to recover by just existing and I wasn’t really enjoying life at all.

HITTING ROCK BOTTOM

One day at work, I had a panic attack in the bathroom. I had never had a panic attack before but I knew what it was. For the first time, I felt the fear and physiological terror that so many of my patients who I treat day in and day out feel. And then slowly and insidiously, thoughts I had never really had before started to creep into my mind. I started fantasising about crashing my car. I don’t think I wanted to kill myself, but I was desperate to find a way out, to have some time off work. I so desperately wanted to tend to the worsening spiral of insomnia, anxiety and stress and couldn’t see another way out.

No one at work suspected what was going on and I think so many of us can be like that. I can be very good at putting a mask on and hiding what’s going on underneath. At my low point and looking back, I can see I was on the verge of a breakdown. In the end, I think I'm quite ashamed to admit what I did. On the back of seven shifts in a row and feeling totally overwhelmed, I started to very methodically punch my hand hard against my doorframe, tears streaming down my face through gritted teeth. I did it purposefully to try and break my right fifth metacarpal, knowing that as an A&E doctor this would mean a plaster cast for six weeks and a “legitimate” reason to be off work. And I say this very shamefully now.

That didn’t work.

I ended up with a fat bruise, an x-ray in A&E, and an embarrassing cover story about why I needed the x-ray. Something about running and falling into a wall. And then I was faced with the stark reality of having to admit to myself that I was not coping, my mental health was deteriorating. I needed help and I needed a break. It was my wake up call but I didn’t know how to ask for help. I went to my GP, but I wasn’t honest. I didn’t tell her the full story as she knew I was a doctor. I just said I was struggling with insomnia. I felt slightly frustrated, yet not at all surprised by what happened, she just asked what I wanted - antidepressants, sleeping tablets? I don’t know what I was expecting in ten minutes really and that is part of the problem.

I think I’m now telling this story because this can happen to anyone. I had no history of mental illness before this, and I didn’t recognise I was spiralling. I now realise that as healthcare professionals, we are probably the worst at admitting and talking about our own mental health struggles, possibly a result of working in a system that is not designed to support the wellbeing of its staff. I know that I was, and I still am bad at talking about this. This is the first time I’ve done so, and compared to hiking the trail, it’s certainly not easy. But I do really hope that this mentality will change because it’s detrimental not to. In a profession with such high rates of burnout and suicide, keeping things bottled up can have devastating consequences.

MAKING A CHANGE

After this episode, I knew things had to change and made a last-minute decision to go back to Nepal to reconnect back to myself and the people I had grown up around. I nearly didn't go as I was terrified of being alone and after ending my relationship, I realised I'd never really been alone. But I guess that was the point. So I booked the tickets, to force myself into the uncomfortable and the unknown. Nepal was the first country I lived in and it had gifted me my love for the mountains. I trekked the Annapurna circuit in the winter offseason and crossed the Thorong La Pass, one of the highest mountain passes in the world. It was a pretty transformative trip in ways I only realised later.

When I returned to real life, I knew I had to make some big changes to my life and I couldn’t keep going as I had been. The Himalayas had reignited something in me that I had suppressed for so long and Nepal played a big role in building me back up. I started to force myself to do the things I knew were good for me. I signed up for the London marathon and over time, running became a bit of a saviour for me.

I call it my ‘moving meditation’; a time to be out in the elements and discharge any pent up or negative energy. I started cold water swimming and trail running. I also discovered breath work which has completely changed my life and within a few months, I felt like a different person from the one that had gone to Nepal. I started avidly reading and learning about more natural, holistic ways of healing that we don't really get taught about in medical school. This all strengthened my belief in the power of nature and movement, but also how time outdoors with others can nurture connection.

HAVING THE TOOLS TO DEAL WITH WHAT CAME NEXT

When the pandemic hit, I felt like I had much better tools to deal with the stress and initially I tried to do the right things. Running, seeking solace in nature (even in urban East London), breath work, avoiding alcohol, sleeping. I locked down alone while working in palliative care. But slowly the exhaustion crept back and I was struggling to fit everything in when I just wanted to get through the day and forget everything that was happening around us in this ‘new normal’. I saw a lot of death and learnt of family illness all whilst studying for exams alongside work. I could feel things starting to pile up and those very subtle signs of burnout were creeping back into my life. This time I had better awareness and I took preventive action. I applied for and was fortunately granted a sabbatical.

For some time I had also been feeling slightly jaded with how we ‘do medicine’ in the conventional sense, where there is more emphasis on treating symptoms with pharmaceuticals rather than looking at the root cause of illness and focusing more on holistic and lifestyle-related therapies. Knowing there was light at the end of the tunnel, I planned a year of self-development, learning more about lifestyle medicine and seeking more adventures in nature. This is part of what led me to walk the Slovenian Mountain Trail.

I was attracted to this challenge as I'm half Slovene and my father is my connection to the country. After my experience in Nepal, I knew I had a deep, subconscious yearning to solo hike something longer. I wanted to push myself physically and mentally and see what I would learn along the way. I haven’t seen my Dad in nearly ten years, but recent news about his health led me to want to reconnect back to my roots and have a longer period of time alone to think about and reflect on this difficult relationship. I have happy childhood memories, and I remember idyllic childhood holidays swimming in the mountain lakes, camping, foraging for mushrooms in the forest. I thank my dad for introducing me to mountains from a young age. But he is an alcoholic and when I was younger I was embarrassed by his drinking and ashamed of what he'd done to our family. I didn't talk about him, I lied about him to friends, I even made up a job for him if anyone asked. When he left, I vowed that I didn't need him and that his absence in my life wouldn't affect me in the slightest, but suppressing, numbing and using unhealthy coping mechanisms will eventually catch up with you.

DECIDING TO HIKE THE SLOVENIAN MOUNTAIN TRAIL

So the decision to hike the trail was quite a personal one. It was very last minute again, which is typical of me. Three weeks after I made it, I was on the trail. I had certainly never done anything like it before, and I truly don't think I knew what I was letting myself in for! The statistics are daunting. The trail is 617 km in total, and with an elevation gain of 37,000 (ish) metres, I would be climbing the equivalent of over four Everests stacked on top of each other.

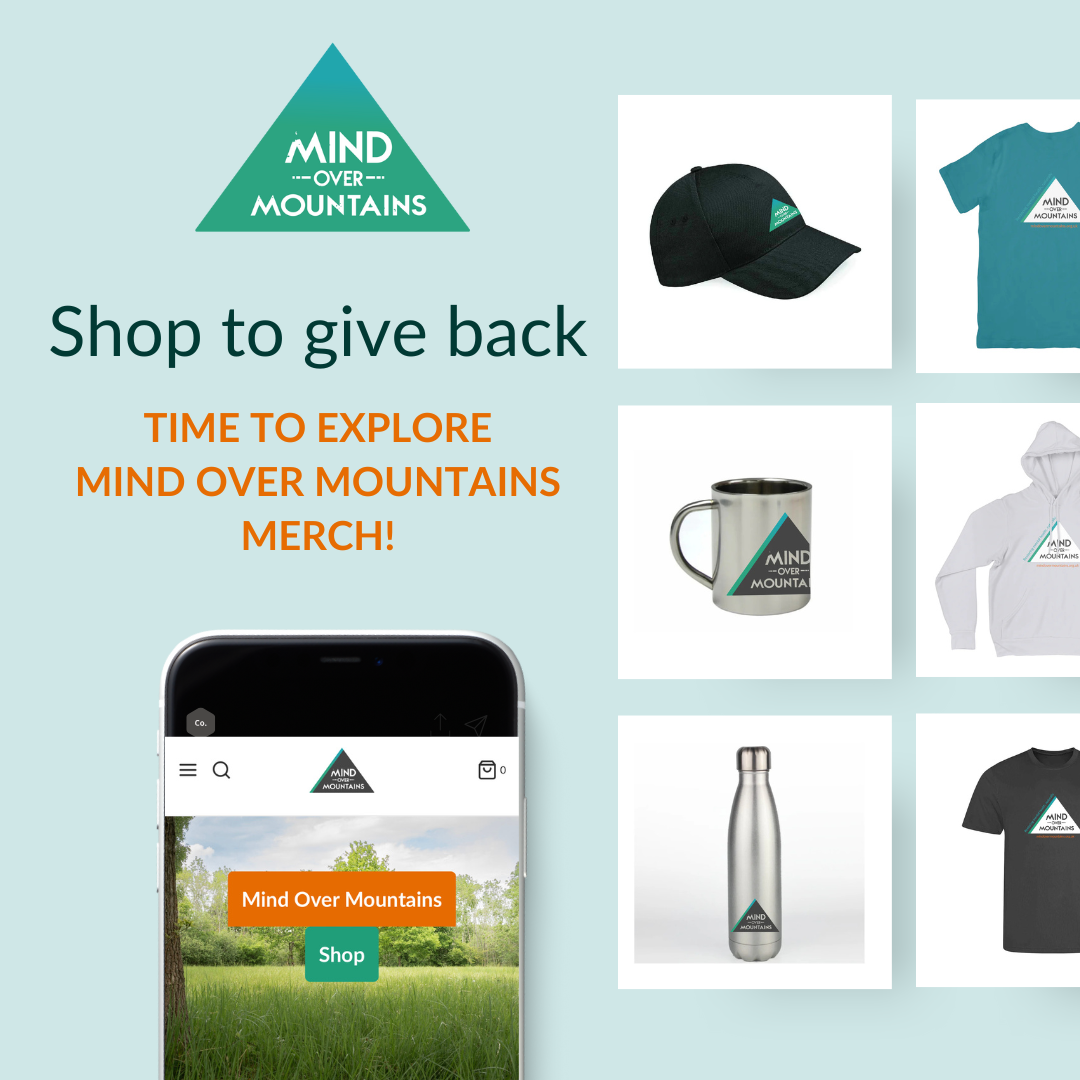

The route takes you over the three mountain ranges of Slovenia- the Kamnik Alps, the Karavanke Alps and the Julian Alps, before winding down and finishing at the Adriatic sea. Thanks to my very poor navigational skills, I definitely ended up doing a bit more than that. I wanted to also raise money for a cause that was close to my heart and Mind Over Mountains resonates strongly with what I believe in. Nature and walking have been so instrumental in helping me through difficult periods in my life and there is so much evidence that spending time outside with people in nature significantly benefits mood, lowers stress, improves confidence and builds resilience.

Here’s my montage of some of the highs and lows

On reflection, as with any physical and mental challenge, there were highs and lows, both literally and metaphorically. The ebbs and flows became the norm as I never knew what each day would bring in terms of weather, food, terrain or getting lost. I learnt to ride the waves, for each day taught me something new. I fell into the simplicity and routine of daily walking life. There were beautiful sunsets and sunrises and stars and nature and solitude. But there was also the intense ascent, exposed mountain edges, steep climbs and unpredictable weather. It was far more physically demanding than I realised and it turned out I needed more specialist gear than I had. Thrown in at the deep end, I had to quickly learn how to use my equipment and to navigate this thing called fear.

As I slowly got used to manoeuvring paths with a 12kg home on my back, moving felt more natural. I navigated ridges, steel cables and foot anchors with more confidence but some sections continued to instil a healthy dose of fear and I found myself in precarious situations at times. I learnt to recognise my fear and sense the surge of adrenaline early, to be aware of it but to stay completely present and focused on the task at hand. With no one around, I knew I couldn’t let it overwhelm me. “Trust yourself, trust your ability, trust your body” was the mantra I kept repeating. I learnt to breathe through my fear, to stay calm, knowing I had to safely get out of the situation I got myself into. I was grateful for the breath work techniques I've learned over the last few years to bring me down safely.

Food was a big challenge for me. I was somewhat unprepared, and being vegetarian, I quickly found out this was going to be an issue in rural east Slovenia. The glass marmite jar I insisted on carrying quickly went from a luxury item to an essential one, but I was very calorie deficient for much of the walk. My body was screaming out for protein, but I mainly lived off sour cabbage stew and would often go days living off rations of chocolate and nuts. Another big psychological battle for me was the pain I developed over the course of the hike. Towards the end, my feet ached with every step I took. The ache would quickly transform during the day into pain and then into a sharp pain until I had to stop because I could no longer walk. In the last week, I didn't think I was going to finish and it became a daily mental battle.

There were many highlights. Being alone was both a challenge and at times a highlight. I would often hike for days without seeing a soul and went long periods without phone signal. The time allowed me to rediscover my love for writing, another pursuit that I had blocked for a large period of my life, and it gave me time to reflect on the important things in life. I really felt the solitude and the silence of the mountains all around me, once having to wild camp alone above 2000m when I arrived to find the only emergency shelter was locked. But that experience of feeling so small and being totally alone, high above the clouds, surrounded by imposing granite walls was exhilarating, challenging, humbling and what I had come for.

I loved the awesome sense of perspective and seeing the scale of what you can hike. It's an incredible feeling to look back and think, “Wow, did I really come from there today?” and to realise what your body is capable of on foot. It also turned out that connection was so important for me. Even though I was physically alone, I never really felt alone. I think I had a romantic, idealistic notion that I was off to disconnect for six weeks.

But the reality was that I needed connection to get me through it. Calls from friends, but also messages from strangers through Instagram, really motivated me and spurred me on every day. The kindness of strangers I met along the way was humbling, and people went out of their way to help me get out of some pretty tricky situations. I was put up in a couple’s home when lightning storms hit and I was stranded with no accommodation. There was a girl in a hut who felt so sorry that I’d only eaten cabbage stew for weeks that she cooked me a vegetable and lentil pasta. And of course, walking down to the sea and swimming in the turquoise Adriatic waters on that last day made all the pain and hunger worthwhile. The last week was immensely tough with pain, hunger, and heat waves, but the sense of achievement and working through my fears alone is something I am proud of.

Reflecting back on my journey and what my take-home message would be, I think it would be to try and challenge yourself to go to your edge. We all have our comfort bubbles in life where we feel safe, but we all have our edges too. It doesn't have to be a physical or literal mountain edge like I often found myself on. It can be anything - entering that park run, swimming in a cold lake, meditating more, attending a Mind Over Mountains retreat.

But how often in life do we do this? I think we often find ourselves stuck in our bubbles and forget the joy of exploring beyond this. I know that over the last couple of years when I've felt unsure or very stuck, I've pushed and challenged myself to see how far I can venture out of my comfort zone and towards what scares me as that is where my growth has happened. Sometimes just pushing forward and working through the pain and suffering to be able to feel that joy is so important. When I go to my edge, whether it be hiking or a freezing cold swim, that's where I become more aware, more present in life and I definitely know that somehow, I come out differently on the other side.

——

Emma raised over £2,500 for our work, incredible! Feel inspired? If you’d like to fundraise for us you can select us as your charity of choice on JustGiving, if you want any support from us on planning, promotion or just some ideas, drop us a hello.

If you enjoy this guest blog and want more tales of adventure, tips to keep your mind and body healthy, unique community offers and our latest events join our mailing list.

BY EMMA PRESERN